In the last year, there has been an increase in coverage from the media over what they suggest is a crisis of modern men:

"What's the matter with men?" - The New Yorker

"Men are lost. Here's a map out of the wilderness." - The Washington Post.

"Is Masculinity in Crisis?" - The New York Times

What is clear from these pieces and additional recent research is this; young men in today’s society are becoming lonelier, less sociable, less educated, more polarized, and more radicalized.

We are at risk of creating a future of isolated, uneducated, and radicalized men.

In this piece, we investigate why this problem is getting worse for young men, and more importantly, what we can do about it.

Let’s start by checking some data that shows us why that future is not one that any of us should want.

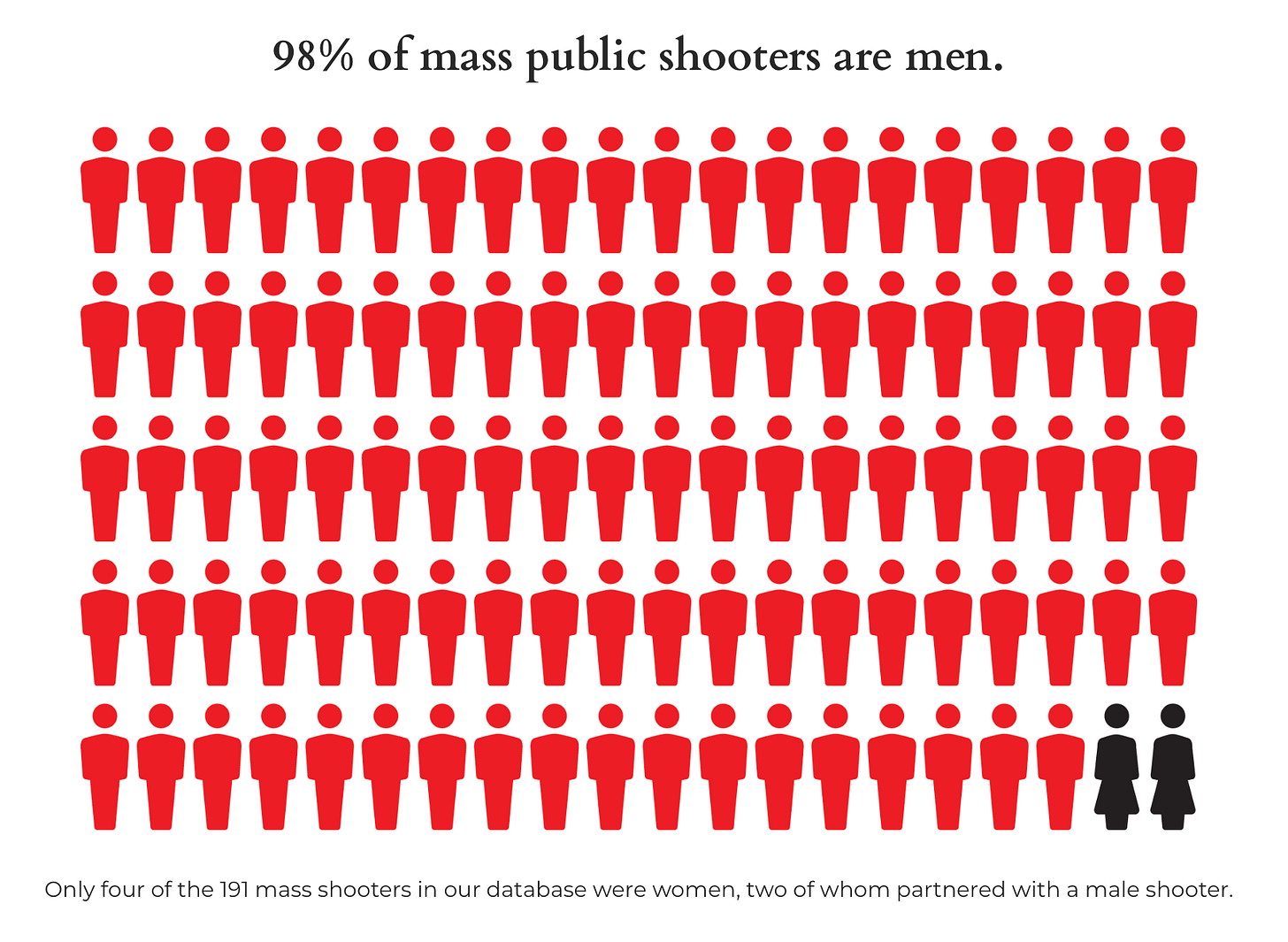

Violence

Of the 172 mass shootings from 1966 to 2021, 98% of those are male.

70% of all school shooters since 1999 have been under the age of 18.

Radicalization

40% of all men say they trust one or more “men’s rights”, anti-feminist or pro-violence voices - compared to nearly half of younger men saying they trust one or more of those voices (source: Equimundo State of American Men 2023).

According to the Equimundo research, 1 in 5 Gen Z men aged 18-23 say they trust Andrew Tate.

Sociability

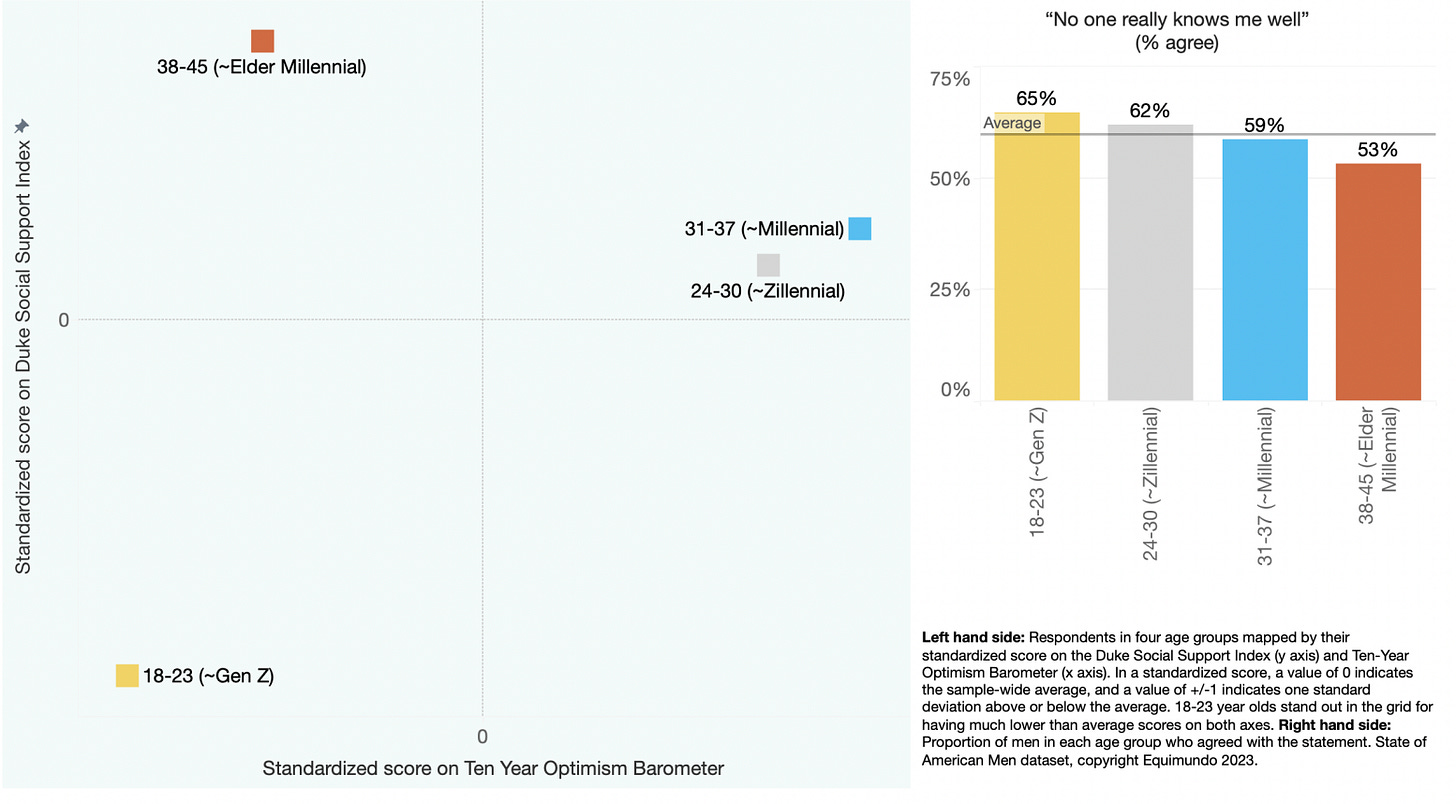

Gen Z men aged 18-23 have the least optimism for their futures, and the lowest levels of social support compared to older age groups.

65% of Gen Z men agree with the statement that “no one really knows me well”.

The proportion of men who report lacking close friendships has surged fivefold since 1990 - standing now at 15%, compared to 10% of women, according to research from the Survey Center on American Life. Men with 10 or more friends have also more than halved since 1990.

Careers and Education

Fewer than 1 in 4 teachers in America are men, down from 1 in 3 in 1980.

Men now only account for 26% of those in HEAL fields (Health, Education, Administration, and Literacy), compared to 35% in 1980.

Male psychologists have dropped from 39% to 29% in the last decade. And for male psychologists aged 30 or less, the male share is now just 5%.

Male social workers have been cut in half to 18%, compared to 36% in 1980.

In 1972, women were 13 percentage points less likely to hold a bachelor’s degree than men. Since then, society has made great progress in leveling college achievement among genders.

However, in recent years male achievement has declined; men are now 15 percentage points less likely to hold a bachelor’s degree than women.

So what? Why highlight the problems of a privileged group?

Throughout history, our society has valued the male experience more highly than other gendered experiences, affording men privilege financially, politically, and socially. This has caused typical male-centric media/research to lead to pushback and may even lead to varying opinions about the focus of this particular piece of research.

At dcdx, we exist to make the future human - and we believe it is also important to identify the areas where privilege may overlap with the challenges facing our collective future.

The danger to our collective future is that young men are becoming lonelier, less sociable, less educated, more polarized, and more radicalized year by year.

This is not a future that benefits anyone.

The Existing Diagnosis

Existing research on this topic tends to point out two predominant factors underlying the evidence above.

Changing Gender Roles and Expectations: Because men no longer hold the traditional norms of “pro-creator, provider, and protector” there is an undefined identity of “manhood” today. While for some men this feels liberating, there exists societal uncertainty over what being a man ‘should’ be today.

Lack of Uplifting Role Models: The culture today around ‘masculinity’ is splintered, and role models that outline what it means to be a man are either hard to find or radical, misogynistic, and anti-social. Look up “masculinity” and you’ll most likely find the new-ish internet-famous personalities like Jordan Peterson and Andrew Tate. Public role models that outline a view of masculinity without scapegoating women’s progress are hard to find.

The Gen Z lens: Why this problem is getting worse.

While there is an abundance of existing literature on this topic, the vast majority fails to account for the ways in which the tools, values, and challenges shaping society today act as catalysts for these trends.

We believe that by looking at these problems through a Gen Z lens, we can uncover a deeper understanding of why this is happening, where it may be going, and what we may be able to do to reverse these trends.

Catalyst 1: The Algorithm

“My FYP knows me better than I know myself”. We see this all the time in TikTok comment sections and hear it endlessly in our research.

This hyper-personalized internet of today can deliver us feeds that match our exact interests - and sometimes even deliver us things we like, even before we know we like them.

It is this hyper-personalized internet that has become splintered with niches and micro fandoms, giving every single online user the chance to find and embrace their own communities.

And it is this same internet that is dangerously good at fortifying echo chambers, prioritizing attention over truth, and making us believe that what we see most often is what is true.

And those elements are no different when it comes to masculinity.

From traditional (outdated) notions of toughness to evolving concepts that emphasize emotional intelligence and inclusivity, the internet exposes Gen Z to a spectrum of identities that manipulate - but never challenge - their understandings of masculinity.

It ranges from one end of “masculinity” with #FemboyFriday, to the other end with trends like The Sigma Male, the Primal Male, the #MonkMode male, and of course, Andrew Tate (and related) content.

This “splintering” further complicates the challenge of creating a collective vision of masculinity that would be important for us to move forward.

Catalyst 2: Modern Loneliness

In May, the US Surgeon General declared loneliness an epidemic:

“Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation has been an underappreciated public health crisis that has harmed individual and societal health. Our relationships are a source of healing and well-being hiding in plain sight – one that can help us live healthier, more fulfilled, and more productive lives,” - U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy.

But Dr. Murthy was certainly not the first to point this out. Early this year, the CDC released the findings from a 10-year Youth Risk Behaviors Study, and revealed to us the following statistics:

42% of high school students felt so sad or hopeless almost every day for at least two weeks in a row that they stopped doing their usual activities. While females show significantly higher percentages across these behaviors, males too have shown increases over time for the majority as well.

The problem is this; while men may report lower levels of concern with mental health, accompanied by research that shows they have fewer close friends and the majority feeling like no one really knows them, men are turning to online communities to solve their search for belonging.

The Equimundo research shows us that men who adhere to what they call the “Man Box” - a set of widely held ideas that men should dominate female partners, not show vulnerability, and use violence to resolve conflicts - show the highest sense of purpose in life.

On the contrary, men most outside this “Man Box” - what we would label as most “progressive” in today’s society, report feeling the least sense of purpose in life.

While some figures and viewpoints may be propagating harmful or “toxic” views, they also give young men a place to feel purpose and belonging.

This - paired with the ability of the algorithm to polarize and reinforce beliefs through echo chambers and content bubbles - makes for a powerful venus-fly-trap-type attraction and captivity.

Lonely young men are either getting lonelier or addressing their loneliness. But right now, the only solution to address loneliness that gives men purpose also confines them to anti-social ideologies.

What can we do? What’s next?

The conversation around masculinity must not be dominated by those who continue to sell men toxic and anti-social ideas, promises, and futures.

The challenge we pose to you:

How might we shift the conversation - not by just pushing against toxic elements of masculinity, but also by pulling towards more positive and uplifting ideals?

Reshaping masculinity on a mass-cultural scale is a huge ask.

But, we can start with these building blocks to address this issue:

Acknowledge the worthiness of the conversation: young men are becoming lonelier, less sociable, less educated, more polarized, and more radicalized year by year. And that is not a future that benefits anyone.

Be visible and start conversations - pull the conversation towards more positive, uplifting ideals of masculinity that help give young men a sense of purpose.

Be proactive in generating solutions:

Highlight positive male role models - give young men positive and “masculine” people to look up to that help them feel heard.

Center positivity, not rejection of negativity - young men need to see what masculinity should look like, not just what it should not look like.

We believe if we start here, we can begin to move the needle. We believe that through this, we can not only continue to uplift and center females but also uplift men.

If we want to make the future human, progress does not need to be zero-sum; it cannot be zero-sum.

And that future?

It is ours to make.

This piece had a range of contributors both within and outside the dcdx team, and would not have happened without each of their contributions and thoughts.

Special shoutout to Mara, Amira, Natalie, Billy, María, and Lily for their help in shaping this work.